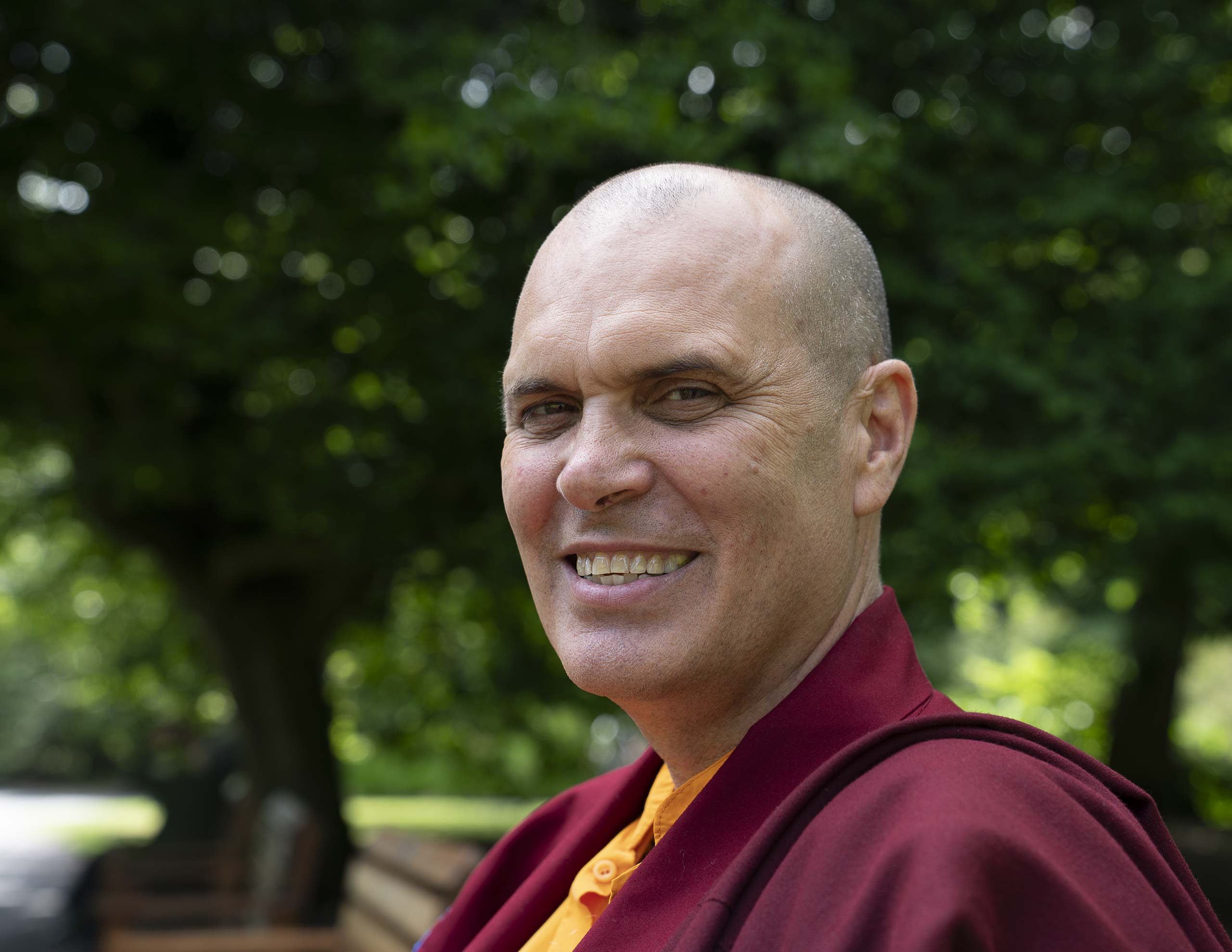

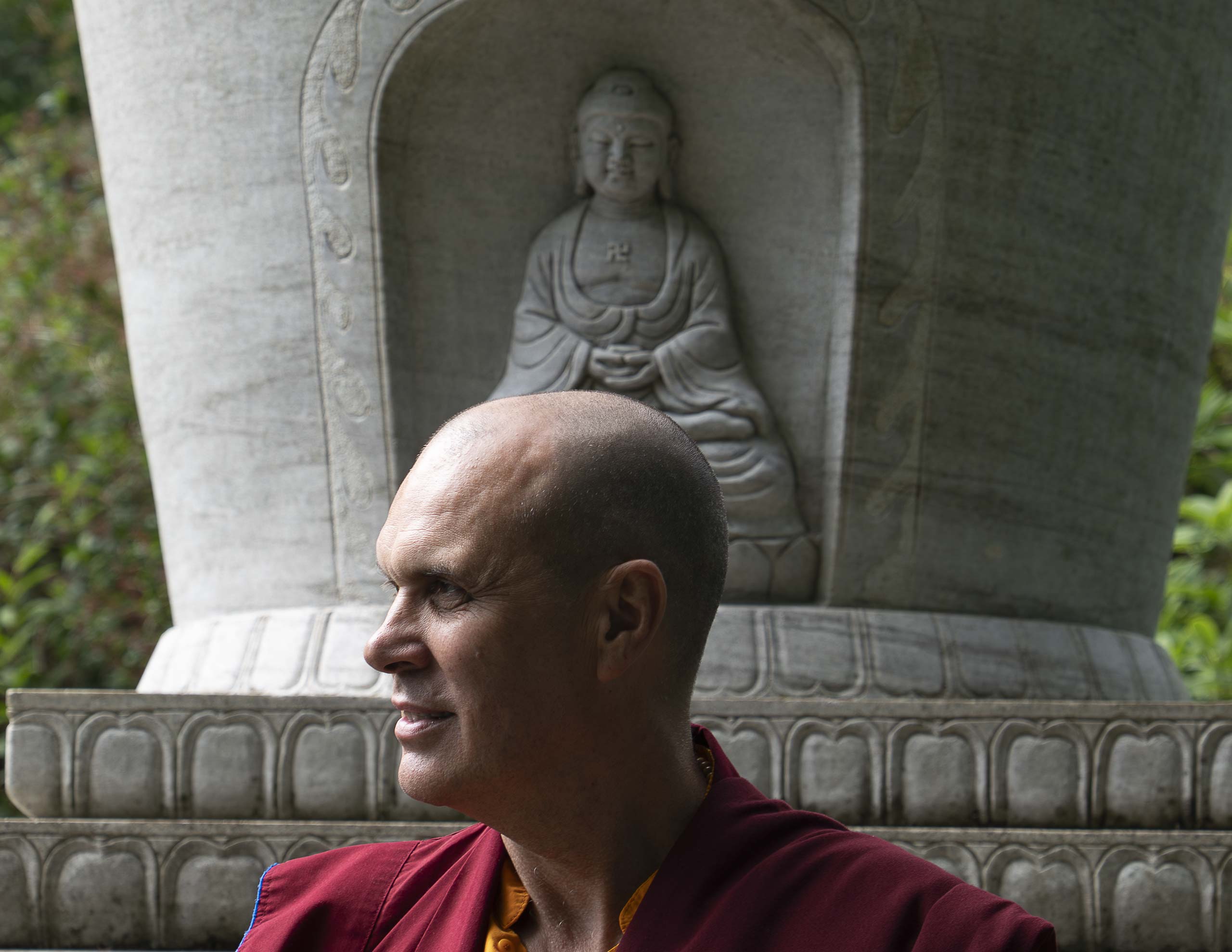

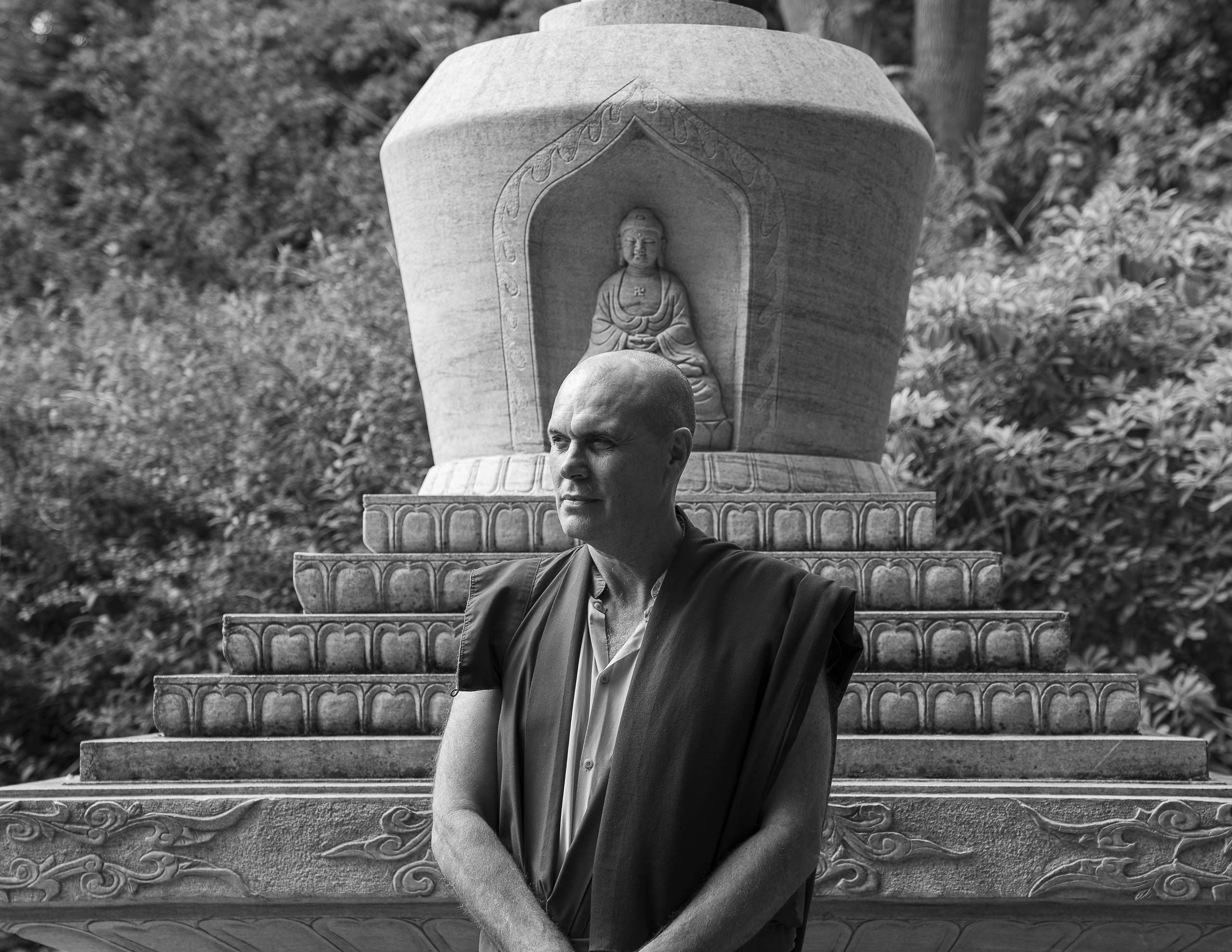

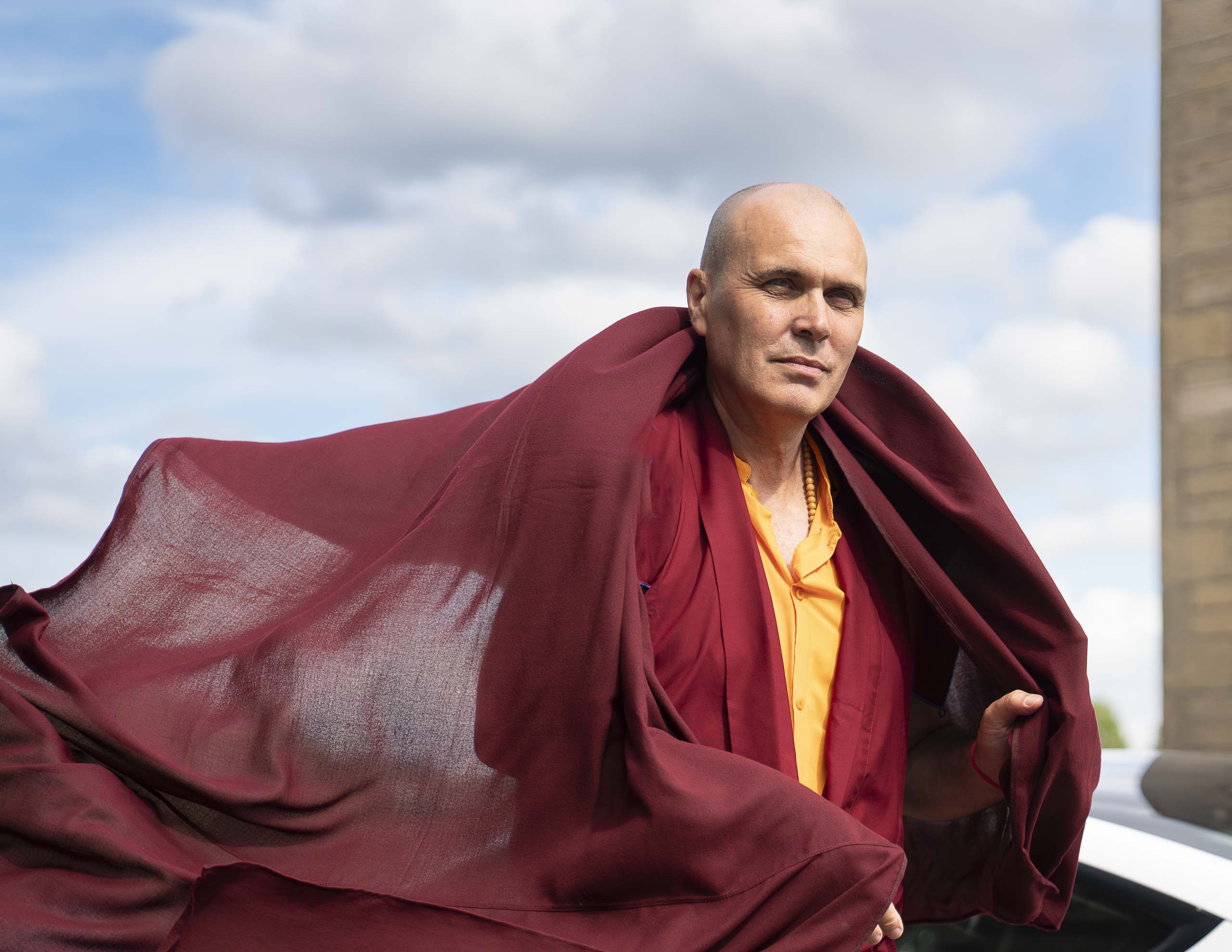

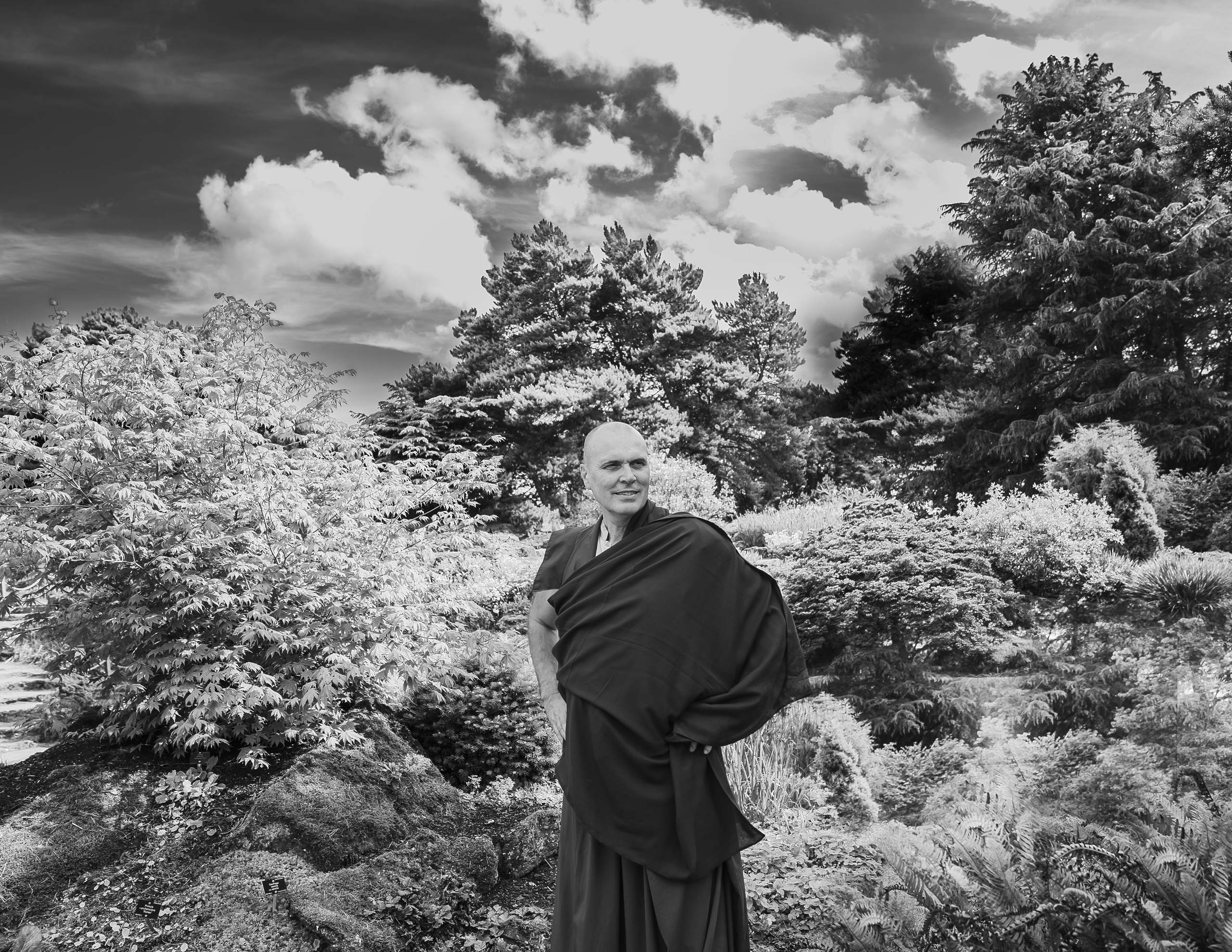

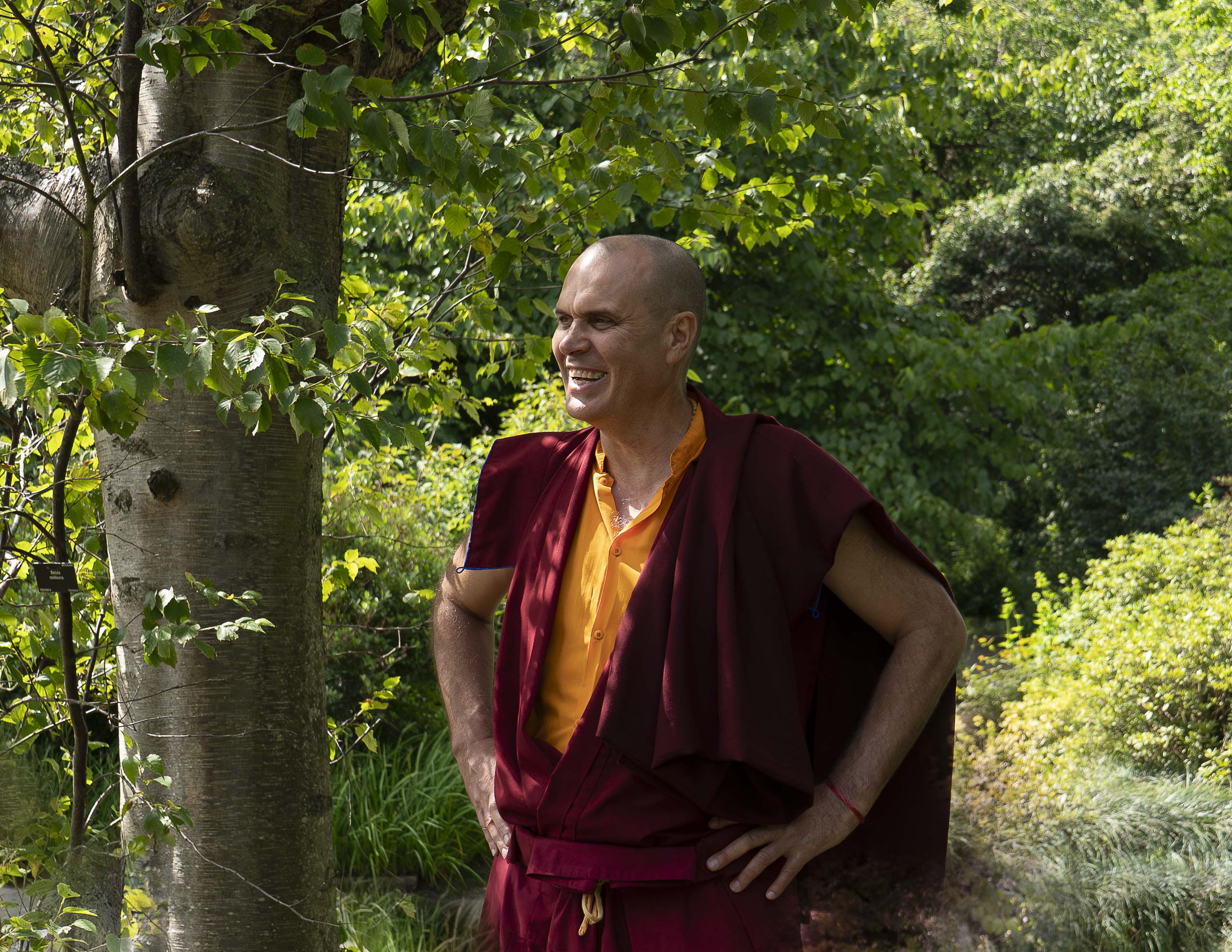

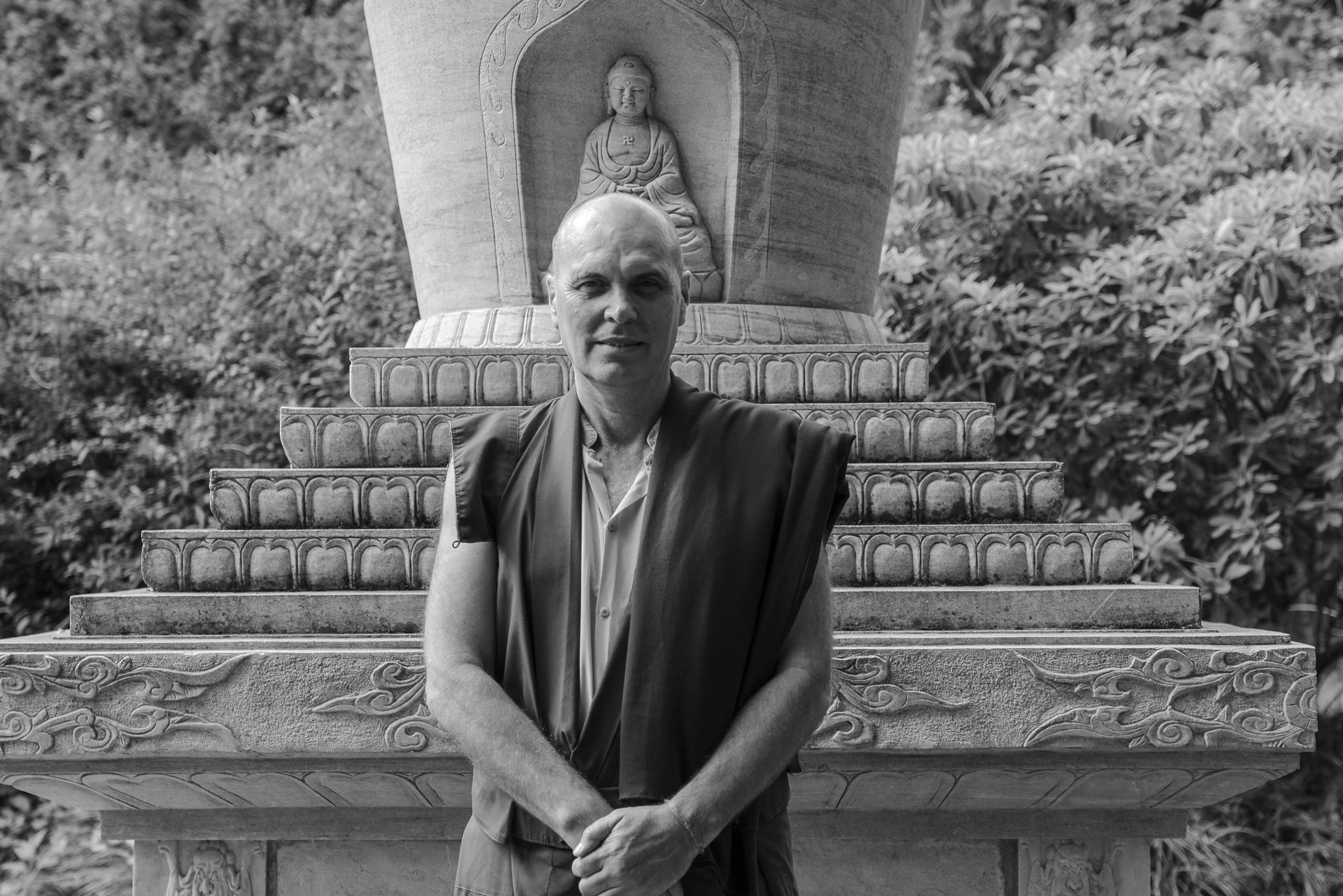

Choden

Choden (also known as Sean McGovern) was born and raised in South Africa. He initially trained as a lawyer before turning to Buddhism. Choden later chose to become a monk and a Buddhist teacher.

He is an Honorary Fellow of the University of Aberdeen, teaches on their Postgraduate Study Programme in Mindfulness (MSc) that is the first of its kind to include compassion in its curriculum. the author of several books, and a co-founder of the Mindfulness Association. He is also a recognised teacher of the University of West Scotland and teaches on the Master of Science teaching Mindfulness and Compassion.

You studied law, but then decided to become a Buddhist monk. Please tell us what happened. What was the trigger for this shift?

It was a long time ago now. About almost 30 years I was living in Cape Town in South Africa, and I was attending law school. And one of the teachers, professors, he was a professor of criminology, one day gave a talk on Buddhism, outside of the university. I went along to this talk, and I was so struck by the way he was talking about Buddhism, and about working with the mind, and transforming the mind.

And I remember thinking: «This is what I am interested in, not law». But I had almost finished my law degree, so I thought I had better finish. My father had paid for it. To make the old man happy, I completed it. But then I made a very strong connection with this person called Rob Nairn and started learning meditation and going on retreats. It was just something that kind of happened.

I then completed my law studies and got admitted as a solicitor.

I worked for a couple of years, just to get my full professional qualification. But then once I did that, I just left the country, and came to Scotland, and didn’t go back. I just left my law career, and studied and practiced Buddhism, and then did a three-year retreat, which was very intense.

After that, I wasn’t going back to law. I chose well, really made the right choice.

You left the monastery and started teaching; you wanted to have an impact and you founded the «Mindfulness Association».

I co-founded it.

I think the idea about being a monk, going back to what you asked, is you keep that robe, even when I travel around, it gives you a certain self-contained space of purity and depth from which to teach. It can be helpful in this crazy modern world where you pulled out of yourself so much.

The idea was to draw on the depth and wisdom of the Tibetan tradition and to offer the teachings in a way that were not dogmatic or religious, but it was like the real wisdom and the methods for anybody, everyday people.

So that was the kind of idea.

Because Tibetan Buddhism is a bit like Catholicism or the Greek Orthodox Church. It’s very rich and complicated.

We decided, we’re going to offer the wisdom, the jewels, to anybody.

And it worked really well actually. I do a lot of my teaching coming out of the more mindfulness approach.

And I think it really works well for modern people, because a lot of people don’t want to buy into a religious tradition and take on board all kinds of stuff.

So that was the reason for setting it up.

So that’s kind of what I’ve been doing the last 12, 15 years: teaching mindfulness, just mindfulness for everyday people.

What sort of advice you have for us the everyday people?

I don’t think one needs to necessarily meditate for an hour every day. You can do maybe even 20 minutes or 30 minutes if you can. But I think the most important thing is to bring the awareness into your life. The sitting can help, but it’s not the most important thing. The most important thing is: Can we cultivate self-awareness, not be constantly pulled into negative thinking? Can we learn to accept all the different parts of ourselves? Can we give ourselves some kindness? These are the things that are really important.

Self-compassion, because people are often so critical of themselves. That’s useful for everyday life, to be more self-contained, aware.

So thoughts don’t just pull you away, you’re more focused on what you’re doing.

You cultivate some gratitude for the good things, compassion for the hard things. It’s all about that. And I think that can filter into just the way you live.

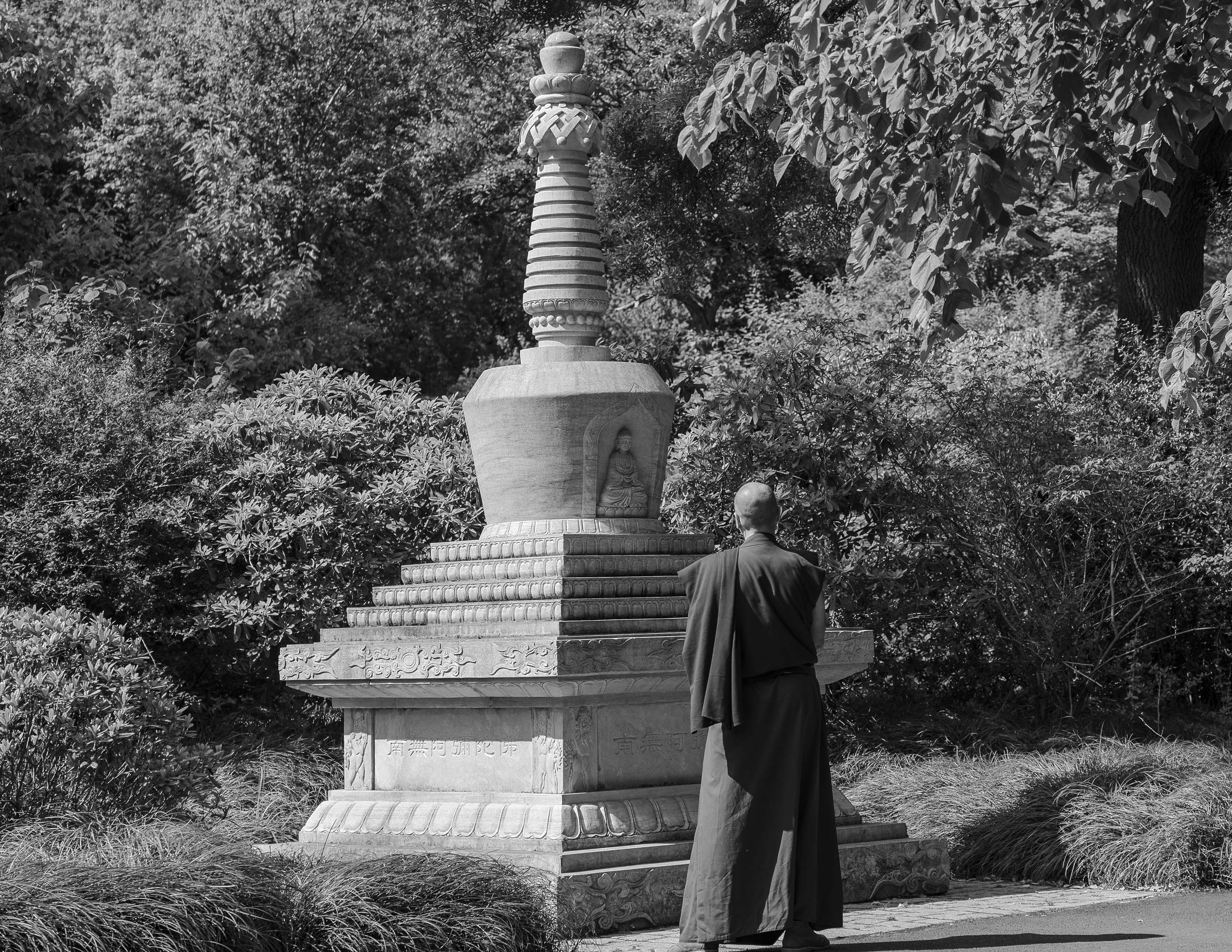

The most important thing isn’t sitting for an hour every day by a shrine.

But the real idea is all of your life is your shrine; you try to see life as being sacred and you relate to people with kindness. Maybe making all of your life your shrine is the real meaning of this stuff.

It is important to first see this life as being a very precious thing and a thing that quickly goes by. This life is very precious and quickly goes.

See if you can wake up in the morning with a real wish to live this day to the fullest. In order to live this day to the fullest, you need to be in the present. You can’t be worrying about the future or dwelling on the past. See if you can try to be in the present moment.

For one, treat yourself with respect and kindness because it’s not easy for anybody to be nice to themselves.

It’s hard to be in your own skin. Be kind to this person that you are because many things have shaped you.

See if you can have gratitude for the little things, the small things.

The little things are the most important things. I don’t know, whatever it might be. Your little cat or dog or walking by a river and the sun is shining and enjoying your cup of coffee. Really appreciate your connection with your loved one before you start having an issue about something.

The small things. I would suggest that. Nothing too fancy but something along those lines.

Do you have a vision or utopia for yourself and for all of us?

For one, I hope we can get this place near Glasgow. It’s a beautiful location and set up this little Buddhist community which will be a wonderful place for people to come just outside the city to recharge, practice mindfulness.

Both for myself, I’d like to be there and for other people.

For myself maybe just doing what I’m doing now. I don’t have an ambition to become famous too much. That doesn’t necessarily help, it makes it complicated.

I think just continuing as I am now. That is part of the mindfulness thing. Maybe moving a bit less. I’m travelling too much. Maybe travelling a bit less, being in one place, having more people come to that one place rather than me flying to other places.

For all of us, that’s a hard one because right now looking at the world and the leaders we’ve got and what’s going on in the Middle East and in Ukraine, it’s troubling. Very, very troubling. It’s really hard to know what to say about the world.

Maybe you need enough people who take care of this earth, the environment. That’s so important because that’s been more and more pushed to the side.

People who really value compassion for themselves and other people and the environment and other life forms.

That if we can have a kind of compassion that’s not restricted by tribalism, human beings are very tribal. Tribalism is very destructive. The Middle East is a classic example.

Compassion beyond tribalism, where we can look after others who are just like ourselves, other life forms, the environment.

Maybe that is a direction we just have to go in. If we don’t go in that direction, I don’t know where it goes.

«Treat yourself with respect and kindness because it’s not easy for anybody to be nice to themselves. It’s hard to be in your own skin. Be kind to this person that you are because many things have shaped you..»

On teaching

What is the difference between awareness and mindfulness?

I think mindfulness is paying attention to what you’re doing while you’re doing it. You are in the present moment. It’s more about attention, awareness is more a bigger space, you know. Awareness is more a bigger space, whereas attention is how we focus, awareness. Mindfulness is a bit like training the messenger, which is attention. We always attend into things to bring it under our control. So we’re not constantly pulled out of ourselves. And then awareness is more a bigger space you can learn to inhabit.

Awareness is a kind of big space, whereas our attention not to constantly follow mindfulness is about learning to train all sorts of things. And it’s more punctual. I’m doing this, I’m mindful of this and awareness is like a lifestyle, sorry, to use this word. It’s, the words are often used interchangeably, but mindfulness is learning to stay in the present moment with whatever you’re doing, you know.

Real life happens in the present moment. It doesn’t happen in the past or in the future.

If you learn to stay in the present moment, you appreciate more, you’re more effective. And when you’re in the present moment, you realize there’s a big space to life I can be in. Most people are very narrow focused. Whereas when you’re more relaxed into the present, the present is big, there’s all kinds of beautiful things we can notice and partake in. Whereas if you look at most people, they just tunnel vision. They’re worrying about the future dwelling on the past.

Mindfulness, come in for the present, breathe, relax, be curious. And life is a big thing, a wonder we can be part of, something like that.

So that’s kind of the difference between mindfulness and awareness.

Your teaching is not ending with this approach to mindfulness, you have next steps.

We have four stages.

The first one is mindfulness, where you’re training your attention not to be in the past or in the future, but in the present.

And when you’re in the present, you have a quality of accepting how you are, be curious about what’s there. So that’s mindfulness.

The next one, the second one is compassion, which is really learning to be kind to yourself. That’s often what so many people need and lack, self-kindness. In many of our courses self-kindness is the big thing, because people are so not kind to themselves.

Then we go to kindness for other people. There’s kindness to self, kindness to others. Compassion for our reality, compassion for self and others.

Then the third stage, insight, is trying to understand the habits that rule our life. There are often deep habit patterns and belief systems that are shaping how we live, how we think. And many people don’t see them.

But actually, often their whole life can be affected by this, like some people are always trying to please people or be a good girl or a good boy.

Insight looks at the deeper habits that are often ruling us. They rule us. These internal patterns that we often don’t even know we have them. Because we act the same way and we are wondering why this happens again. Because what is internal happens and I think the first step is to get to know them. To know I have them is really important because we are not aware.

Why do you call it compassion and not empathy?

Empathy is, I think, empathy is you get a sense of what somebody else is going through. Maybe I look at you and I get a feeling of what’s going on for you. And maybe I sense your suffering or your pain and that somehow touches me in some way.

Compassion is the response to empathy. I really look at you. I mean, I don’t know you, but I might get a feeling about something going on for you and I get a sense of what it’s like to be in your shoes.

Compassion is a real response of loving kindness, care, something like that. Empathy is part of compassion, but you need the second one, the response.

Otherwise, you can get a kind of overexposure, overexposure to suffering which can burn you out.

Compassion is sort of after empathy.

You can do things yourself to change the way you are. But It’s very hard to actively change somebody else. All you can do is provide them with a very loving, supportive presence and maybe have some suggestions.

You can take the horse to the water, but you can’t make it drink. There’s also a thing which is quite important in mindfulness, it’s not trying to fix people. Not trying to put them right. It’s more like, just offer them a very loving, supportive presence, that helps a lot. It’s really best if people themselves decide when and how they’re going to change.

Mindfulness is without judgment; that is an important point.

Because if the other feels that you disagree with, we have no hope.

Judgement starts with you. The mindfulness starts with oneself where you don’t judge the different parts of you. You just hold them in a very kind awareness. So again, awareness is a bigger thing and you’re really aware what’s going on in the different parts of you. And you hold it in a very non-judging kind awareness, very important. And then with other people too, you sort of get a sense of somebody and it’s very important to not judge people. Because for one, they’re judging themselves so much anyway, you don’t want to add your judging to them.

Your input is teaching, and you have also a connection to Aberdeen University?

We’ve had a long collaboration with them, going back to about 2011 where we started a Master of Science in Mindfulness. Official, postgraduate Master of Science in Mindfulness.

It started in 2011, and it’s had a lot of interest. A lot of people signed up for it.

Because there were some others too, Oxford University’s got one and there’s one in Wales called Bangor.

And I think our one had compassion in which made it distinctive. We taught both mindfulness and compassion. The further steps we also taught. Insight. We taught three steps, whereas most places just taught regular mindfulness.

A lot of psychologists, social workers, educational people, businesspeople, a lot of people have done this degree. It’s been a real success over the years.

Who wants a Master in Mindfulness?

Psychologists and everybody could use it to deal with this. But I think people do it partly for themselves and partly because in psychology now people draw a lot on mindfulness. Social work too. A lot of them find a way that mindfulness benefits their professional life and it benefits themselves. Those two things.

About celibacy

In my case, I only became a monk after being a lawyer, I mean, I had a life before, I had quite a number of different relationships which I can then draw on that experience to help others in difficulties in their relationships.

If you want my honest opinion, I don’t think the celibacy thing works in the West. I don’t think the monastic thing works in the West. It’s like a dying breed, you know. I mean, sometimes I wonder how come I’m still a monk, you know. And I totally agree with you. I think in the West it’s so different, you know, that a lot of us carry kinds of emotional wounding and things we need to work out. And often we need to work it out in relationship through love and connection. So, if you just remove that, you remove an area of growth. I’m almost arguing the same point as you. I remember my brother once saying to me, «It’s your bad luck you’re a Tibetan monk, not a Zen monk». Because Zen monks aren’t celibate and Tibetan monks are. So, for me it’s a dilemma.

Because I didn’t find relationships easy. Well, maybe nobody does.

The dilemma for me is whenever I was a monk, because I stopped, I did it one year and stopped. Generally because I met a woman I liked. Then three years and then I stopped. And then I took life. So, I did it three times, which you can do.

But whenever I took the robes, I found some internal light went on. Something, it was a touch, something in me, which is how I put it into words.

And for some reason when I was a monk, I felt this kind of lit up feeling of happiness and joy, which wasn’t dependent on anything.

It is the term sukkha in Buddhism. A feeling of joy and peace, not dependent on things you have, people you are worth. And that’s like a relationship.

And I felt this kind of happiness.

But then when I stopped being a monk, that light went out, I don’t know why. And often I would lose interest after a while in a relationship. Because I had this monk, I think in my understanding, maybe in my past life I was a monk in Tibet. I don’t know. I’ve been trying to understand it for a long time.

Often, there was something special about it that I could only talk about for myself. I wouldn’t generalize for other people.

Like some internal light went on that was not there when I wasn’t a monk. That’s why I stay as a monk. I don’t need to be a monk. I could still teach my stuff as a layperson. But I agree that for most people the celibacy doesn’t work. And they may be monks for a couple of years and then stop because they can’t sustain it. And they’re drawn to have relationships. And that’s okay, you know.